As a part of the most recent revision of Cairn’s curriculum, a new civics requirement was added to the array of courses that comprise the University Core, classes that all students take regardless of major or program. The rationale for the inclusion of POL 101: United States Government and Civics in the Core is tied to our mission; we want our students to serve well in society as good citizens and neighbors. This mission is rooted in our theological and philosophical commitments and is integrated throughout our various programs and courses. Cairn also developed its new Core Curriculum based upon a broad assessment including deficiencies in the existing Core, as well as changing student needs,

knowledge, and sensibilities. The broader social and cultural shifts for which students must be prepared were also considered. In the University’s judgment, civics instruction was missing, and civics knowledge is needed.

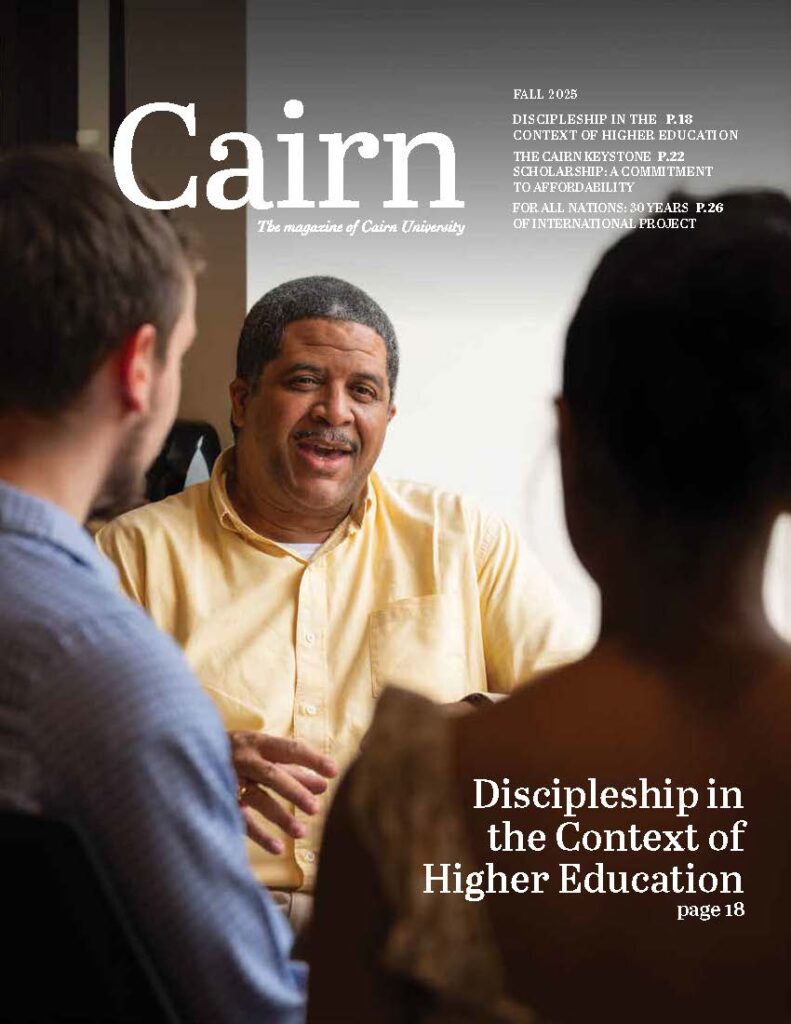

When I was a student at Cairn University a little over 30 years ago, I took a political science course, which was not required for my program. While it was a requisite course for students in a number of majors at that time, for me it was an elective, something I was interested in, and something I believed would benefit me in graduate school and beyond. It was a 400-level course that had a significant amount of reading and writing required. The content of the course was largely historical and philosophical, building upon my studies in theology and Bible, and provided an opportunity for the integration of my knowledge in those subjects, as well as history and the social sciences. This course was ably taught, extremely impactful, and did much to sharpen my analytical skills, biblical worldview, and perspective on the dual citizenship dynamics we navigate as Christians. To say I was thrilled to be assigned to teach that class when I joined the faculty a few years later would be a gross understatement. Taking that class and the subsequent work of teaching it (and the other social science courses I was assigned) from a biblical perspective has been integral in shaping my ideas regarding pedagogy, curriculum, and my vision for the University. I still reminisce with alumni on that class and even the out-of-print textbook, American Political Thought by Alexander Pendleton Grimes. And decades later, I am still building upon what I learned and taught in SO 434. In many ways, that class was the progenitor for the newly instituted Core Curriculum requirement, POL 101. However, that SO 434 class assumed that students had some measure of civics literacy and understanding from prior schooling. And whether or not that was an accurate assumption then, it is clearly not an accurate one today.

That there is a basic civics knowledge deficiency in America today is hard to dispute. The statistics speak for themselves. As the Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ISI) recently reported, 71% of adult survey-takers failed a basic, multiple-choice civics literacy test. Additionally, fewer than half of surveyed Americans could name the three branches of government, let alone discuss the important constructs of the balance of powers or the rule of law, essential components of a thriving republic. But beyond the statistics, our experiences culturally and conversationally make it clear that this civics knowledge deficit is real. Late-night television shows make comedic hay by roving the streets to ask questions of individuals regarding basic governmental structures and legislative processes that are usually met with the most ridiculous and incoherent responses, which is a sad commentary on the state of things despite its comedic value. It is also apparent that people have strongly held and passionately expressed personal opinions and political feelings about the government, political figures, policies, and governmental action, but these are sometimes arrived at or acted upon without a demonstrated understanding of the wiring and working of the system of government the founders and framers created. Opinions abound on things like the electoral college, gun rights, and Supreme Court decisions but so too does a lack of understanding what the Constitution says about or provides regarding those things. For example, there were ample reactions to and criticisms of the Supreme Court’s recent Dobbs decision, asserting that the court was out of touch with public opinion. But that is precisely how the U.S. Constitution defines its role, an objective interpreter of the law not influenced by public opinion or other such forces. Making the case that the Court needs to rule in accordance with the loudest or most prevalently expressed public opinion is flawed at a most foundational level because it rests upon civic “ignorance” in the most technical use of that term. Political tensions and divisions are the highest they have been in most of our lifetimes, and they are only exacerbated by the fact that Americans apparently know less about the structure and function of government than ever before. This dynamic leads to all kinds of social and cultural, let alone political, complications. There is a danger in becoming a self-governed society that is governed by personal feelings and collective emotional frenzy rather than by reason, knowledge, and civic sensibilities.

The aforementioned survey also showed that the overwhelming majority of Americans (71.6%) believe colleges should teach America’s heritage, including her founding documents and the importance of good citizenship. It begs the question, if there is this much consensus around the importance of this subject, why are colleges and universities not taking a more active role? Since this data was made public, we have not seen a significant increase of college-level civics and government instruction; instead, there has been an almost systemic undermining of the teaching of American history, civics, and the significance of the American founding. The data from ISI shows that colleges are not helping matters, since college graduates failed the civics literacy test with an average of 57%, only 13 points higher than those with a high school diploma. It also revealed that only 24% of college graduates understood that the first amendment in the Bill of Rights prohibits the establishment of an official government religion. The number of college graduates who can name even one step in the process by which a bill becomes a law is staggeringly low. How can we expect individuals to assume their important role in the republic as informed and engaged citizens when they do not understand the basic structure and function of the government as outlined in the United States Constitution? It is fair enough to assume that this lack of civics knowledge and an understanding of America’s heritage and founding actually works against a shared understanding of rights, liberties, and responsibilities and is contributing to the social and political tensions and polarizations experienced today. How can educators, at any level, be satisfied with these results and think that they are anything less than an existential threat to the nation, the good society which it was formed to promote and protect, and a thriving and informed citizenry? We are not.

Cairn understood that developing and requiring a POL 101 course like ours would be counter to the trends of curricular development in other higher educational settings. However, it determined that the civics course it created and required was a good response to both the void that exists presently in primary and secondary education as well as the diminishing civics literacy and participation being observed in the broader culture. These two realities converging with a media-driven rise in factious social and political vitriol and activism are dangerous and present exactly the kind of dilemma the founders and framers believed education was suited to address. But in order to assist with social order, education must be responsible both with regard to its intentions and objectives and also what content it will actually teach.

The POL 101 course at Cairn was born out of genuine concern for society and a commitment to mission, but it also has a simple and coherent design to teach students what the republic is and how it functions. The course is not designed around emotional or ideological reactions to current events, political or social agendas, or partisanship. It does not feed the identity politics of the day or assume an inherent injustice in the Constitutional Republic so meticulously framed by those men whose knowledge of history and human nature shaped a government built upon universal principles and natural law. The course requires students to read the Declaration of Independence, the United States Constitution, and several other original sources such as the Magna Carte, portions of the Federalist Papers, and several U.S. Supreme Court decisions. The course also requires students to satisfactorily answer questions taken from the U.S. Citizenship exam in order to pass the course.

Cairn’s POL 101 is divided into units that build upon one another and culminate with a consideration of the responsibilities of an informed citizen. It begins with an examination of biblical anthropology, because what we believe about human nature and the basis upon which we believe it shapes our understanding of the nature of politics, why government is necessary, and in what form it best facilitates the expression of the divine image in which we are created while restraining the evil we are prone to as a result of sin and the fall.

The course also discusses the development of ideas ranging from individualism to constitutionalism and provides a philosophical and social context for a survey of the history of the American founding and the Constitutional Congress’ work that required great statesmanship and compromise to build a lasting republic rather than a fragile pure democracy that might be given to tyranny or mob rule.

Students work through the Articles of the U.S. Constitution that define and limit the government, provide structures and clarify functions, and balance power between the branches of the federal government and between federal and state governments. Students examine each branch, how they work, and the relationship between them before examining the Bill of Rights, discussing the Amendments and the debates about how to interpret the Law of the Land that are tied to an understanding of the fundamental and essential concept of the rule of law. Cairn students learn what the Constitution says regarding elections and representation. They learn why the electoral college was created and how it works so they can decide for themselves whether they think the benefits outweigh the liabilities. Students learn that rights are not given by the government but rather are to be protected by it, that if rights are granted by the government they can be taken away by the government, and that individual liberties are the truest measure of equality according to the Constitution.

The course is not designed merely to inspire students to vote to “be a voice for change” but to teach the importance of the concept of self-governance, the fragility of it, and its expression and preservation through voting as expressed by the framers of the Constitution. These technical aspects of the founding and civics are essential not only in forming students’ political attitudes but also their own sense of responsibility as citizens. The exercising of citizenship is taught as a form of stewardship, that the blessings, freedoms, privileges, and responsibilities we have as citizens are not to be squandered or taken for granted any more than time, money, talents, or opportunity. America’s fifth president, James Monroe, once wrote that “the question at the end of each educational step is not simply what has the student learned, but what have they become.” Students becoming informed and responsible citizens is a noble end, and civics education may prove to be an effective step toward it.